Last week, Booknik read books by Guillermo del Toro and Daniel Arnaud, analyzed the tumultuous biography of Ayn Rand, answered questions of the What? Where? When? quiz festival, inspected fateful photos, munched olives with gusto, wandered Venice, got captivated by the anime about heroic Young Pioneers, and cooked self-styled Turkish salad. In the meantime, Booknik Jr. consoled parents whose kids speak all languages at once, weaved a glass-bead fish, and learned new Hebrew words.

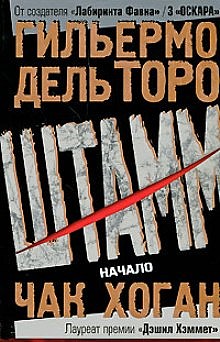

Vampires stand for the human fear of death, and wish for immortality, they are instrumental in gaining eternal life, without demanding any merits, faith, divine grace, or enlightenment. In order to become a vampire, one needs only one, often rather accidental bite, upon receiving which a human parts company with his or her blood, soul, and perishable nature. Del Toro leads his readers into the zone of ancient legend, and present-day frights. You’ll die if you don’t wash your hands. You’ll die if you breathe some poison in the subway. You’ll die if you haven’t noticed your partner’s sickness. You’ll die any which way, slowly, painfully, shedding your own humanity. You can’t be blamed for this, this is purely an unfortunate turn of events. Not your fault. God still loves you, and everyone has a chance for salvation.

Mysterious Booknik reviewer Masha Tuuborg reads The Strain. Book 1 of the Strain Trilogy by Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan, and looks at the vampirism through the eyes of contemporary megalopolis’ overeducated denizens. It turns out, the vampire hunter in the book is Jewish not quite by accident. Jews suffered extermination many times, so they are qualified with necessary patience to bide their time, and with necessary paranoia to notice danger when no one else sees it. Naturally, Abraham Setrakian, the Treblinka survivor, won’t kill vampires with prayer and holy water. There are more effective means.

Opera, Wine, and the Demolished Temple

Nabuchodonosor II, by Daniel Arnaud

Booknik reviewer Yevgeny Levin studies the monograph by Daniel Arnaud who, in his turn, studies not very numerous sources on the life of Nebuchadnezzar the Second. The author readily admits that there remain too little actual biographical data on the king, and this is the reason why the book mostly covers not the king in person but his times, the political life of Babylon, the country’s relations with neighbors, and its religious beliefs. The fantastic career of god Marduk is prominently featured, who used to be a minor village deity, and got elevated through the ranks to become the head of the entire Mesopotamian pantheon. The conquest of Judea is but a brief episode of the king’s rich biography.

So who was he, Nebuchadnezzar? A talented warlord, a great conqueror. He restored a number of cities, fortified the capital, he built and decorated temples, maintained the irrigation, the backbone of Mesopotamian economy. And he seemed to think that he was God, although he never declared it openly.

Where Are We Going, Me and Piglet

El asombroso viaje de Pomponio Flato, by Eduardo Mendoza

In his wanderings, philosopher Pomponius Flatus saw a lot of things, and this is why the main thing for him is not his religion but a good supper and someone good to talk with. Yet in Nazareth, the poor soul has neither one thing nor another. Moreover, he has to investigate a murder. The accused one is carpenter Joseph, and he is to be hanged on a cross. The man’s son Jesus comes to Pomponius promising a reward if the philosopher finds the real killer of rich Epulon. All evidence points at Joseph, and he refuses to defend himself. He even humbly makes the cross for his future execution. Pomponius takes up the case, and Nazareth turns into a schizophrenic American town. The local populace joins in conspiracies, hungry Pomponius suffers visitations from a fox and a raven with a piece of cheese in its beak, Lazarus, alive but ulcerous, propping himself on a crutch, comes to talk, and the philosopher is constantly harassed by crowds of enamored teenagers, and dumb Roman legionnaires. Anyone could go raving mad, but not the man who had traded his good health for finding a river of wisdom. And, certainly, not Booknik reviewer Anna Andreyeva who is engrossed with El asombroso viaje de Pomponio Flato, by Eduardo Mendoza.

…and many other twists of fate in the Books & Reviews section.

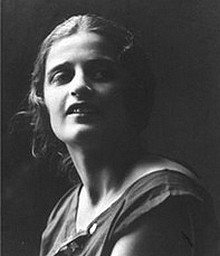

Booknik contributor Elisheva Yanovskaya returns to the well-trumpeted and slightly faded life story of Ayn Rand, the Jewish girl who fled from St. Petersburg to create a theory on the ruins of her childhood, that attracted millions of followers. “Rand is alien to any religion,” she writes, “but if she doesn’t embrace Christian over-altruism proactively, she practically never mentions Judaism at all. Anyway, she keeps silent on her Jewish roots, too. The legend claims that her famous nom-de-plume picked up in America, was the name of a typewriter company. An assimilated daughter of a settlement Jew, she received excellent education but never mastered neither Hebrew nor Yiddish, and she seemed to know Tanach texts only in synodical translations. Yet the truly religious fervor Ayn Rand put into defending her ideals, allows us to presume that she indeed felt that Mandelstam’s scrap of Judean musk in her home’s atmosphere. Perhaps, this is the reason why the traditionally religious redneck America that still had its Protestant principles in the early 20th century, embraced ‘atheistic’ maxims of that ‘reactionary’.”

…and many other stories of wonder in the Articles & Interviews section.

Known gamblers Marina Karpova and Yevgeny Levin tell Booknik readers of the international festival in Eilat. A number of national teams participated, including Azerbaijan, Canada, Georgia, Germany, Israel, Russia, Ukraine, the U.S., and Uzbekistan. Our reporters ask tricky questions, and the readers have a chance of proving they are better than the acknowledged quiz experts.

In October, Bonn, Germany, hosted the exhibition Bilder im Kopf: Ikonen der Zeitgeschichte that featured 11 photographs that signify the history of Germany in the 20th century, as well as the myths they created. The exhibition was put together by Das Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, and commemorated the 60th anniversary of the Federal Republic of Germany, and the 20th anniversary of the Berlin Wall dismantlement. The HDG director professor Hans Walter Huetter counted on the exhibition to demonstrate “key images that were imprinted in the collective memory of Eastern and Western Germans, and defined the nation’s historical conscience.” A lot of historical documents, including photographs, are preserved, yet the history proves that just a few of them become truly symbolic, and the process is, at best, rather curious. Often, the interpretations obscure or change the real context of a photograph. Booknik’s German reporter Anna Cherednichenko visited the exhibition, and she now dissects some myths about those photographs for Booknik readers.

New Songs under Ancient Trees

“What is the Israeli contribution to the world? Cherry tomatoes, Merkava tank, mobile phone microchips, new medicines, UAVs, and ICQ. And olives. Of course, for the Israeli olives are the best.” This advertisement was broadcast by several Israeli radio stations in the end of October, and it was dictated not only by the abstract national pride, and not by the fact that olive branches are present in the Israel state emblem, being the exact replica of Zachary’s vision by the way, complete with a menorah. The thing is, on the wings of first rains, the 15th Olive Festival arrived at Israel. Booknik’s Israeli reporter Ariel Bulstein visited it to tell us about it.

…and other unexpected revelations in the Events & Reports section.

“If you don’t come close to the famed square and the Rialto, flooded with international gawking crowds, the Serenissima is quite passable in the late fall. Tribes of Japanese tourists, processions of German late romanticists, and American landing parties stick to those pastures, and away from them, apart from aborigines, one might encounter only an attractive bearded expat who hasn’t made his choice between Weil and Genis yet, a lost Russian-speaking sheep who has trouble extracting himself from the San Michele graves of Brodsky, Stravinsky, and Dyagilev.” Melancholy traveler Nekod Singer wanders about Venice, writing letters to Signore Hermetta Pierotti the Second about relations between poetry and truth, and life and art in this real yet somehow imaginary city.

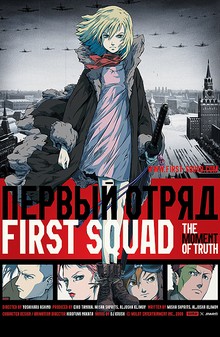

First Squad: The Moment of Truth (aka Fâsuto sukuwaddo), directed by Yoshiharu Ashino

Out of fear to be sued for falsifying the history or the sheer post-modernity, now and then the film creators hint at the fact that all events in the anime saga may well be the product of a delirium of a very sick girl who had lost her parents, and found herself in a hospital with a severe head trauma. This plot line is not dominant in the story, yet it is the key to understanding the film. It seems that First Squad is being concocted by a teenager living in a world where all books and films about the WW2 are somehow extinct, so he or she has to construct and flesh up the myth with anything available. Poster scraps, loose threads of several anime universes, books by Masodov, Anufriyev and Pepperstein, Circus and Alexander Nevsky, Alpert’s Battalion Commander photograph, Bogomolov’s Moment of Truth, everything comes in handy in most unexpected contexts. Only Mother Russia is missing, who could’ve come alive and adopted those heroic Young Pioneers. Strange as it may seem, but the Great Patriotic War still gleams from those bits and pieces of broken toy cars, candy wrappers, and mirror shards. Although they never painted Hell with watercolors, here the object itself seems to call the shots. Even if you compose ribald ditties about the war, you always come to Simonov’s Wait for Me in the end.

Sasha Shchipin whom Booknik is proud to cooperate with, watches First Squad, and thinks about children who kill and die.

…and other blasts from the past in the Columns & Columns section.

Who Are You in the Bible?

The Good Book has tons of characters. Booknik chose a few, and now invites you to try their masks on. Upon completing this test, you’ll know what Biblical hero you look like.

…and many other magnificent masques in the Contests & Quizzes section.

The Colonel from Big Seidemenukha. Part 5

Arkady Perman tells about holidays and celebrations in Big Seidemenukha settlement. In 1927, the unassuming Jewish collective farm was getting ready to meet its future eponym Mikhail Kalinin who was planning to launch the first Jewish national center Kalinindorf, formerly Big Seidemenukha. The farming colony put some effort into the celebration as the local klezmer band got its first serious gig, and was reformed into a brass band for the engagement. Yet the peaceful life of Jewish Serene Field was practically over, for by the 1940s Jewish schools were closing down, and the War was just around the bend.

Don’t Grudge the Brew 25. Self-Styled Turkish Salad

The Turki Salad is really a Mediterranean myth that feeds entire Israel. They don’t even know this recipe in Istanbul or any Anatolian village. Moreover, in Levant there is no clear line between salads, sauces and soups, come to think of it. Any Israelite will find it in a supermarket on the same shelf with tahini, humus and other sauces, and it clearly belongs to the same philosophical category. So, no matter how you look at the Turki Salad, the dish is mysterious and popular, and its popularity is skyrocketing now with the flu epidemic in progress, for it has a lot of garlic in it, together with other healthy ingredients. Booknik’s Chief Chef Roman Gershuni explains Israeli salads again, develops the parsley’s psychological profile, and declared his love for cumin.

…and other tasty tidbits in the Video Blog section.

The Summer Is Gone, the Summer Will Come

Family Booknik, also known as Booknik Jr. goes on with The Summer Is Gone, the Summer Will Come vacation photos contest. Send in your kids’ pics, for the more the vacations are remembered, the sooner the next ones come.

Shall We Rezhem, or In Small Kuskami?

Booknik Jr’s faithful contributor Alena Smiryagin explains how hard it is for a kid to be bilingual, and how kids cope with it when they have to grow up speaking several languages at once.

Training, Taming, and Evasiveness

Cabot-Caboche, by Daniel Pennac

Booknik Jr’s contributing editor Alexandra Dovlatova-Mechik reads the children classic by French author Daniel Pennac, and successfully tries the life of a stray dog on as she reveals some unexpected details on the dogs’ taming of humans.

Tails Wag Dogs with Abandon

The 6-year-old son of the Booknik Jr’s contributor Tatyana Anisimova taught his mother to weave a glass-bead fish, and she will now pass her newly-acquired knowledge on to you and your kids.

What’s for Breakfast?

Zhenya Lopatnik conducts her second Hebrew Lesson for the not-so-grown-ups. As usual, we’ll learn heaps of new words, and won’t stay hungry.

…and other survival hints at Booknik Jr., our family-oriented web site for kids and their parents.

Never let it out of your scopes: Booknik and Family Booknik are supported by the AVI CHAI Foundation.